- Home

- Patricia Horvath

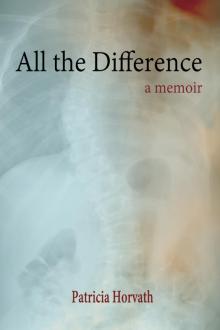

All the Difference

All the Difference Read online

© 2016 by Patricia Horvath

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher:

Etruscan Press

Wilkes University

84 West South Street

Wilkes-Barre, PA 18766

(570) 408-4546

www.etruscanpress.org

Published 2017 by Etruscan Press

Cover artwork by Jeffrey LeBlanc

Cover design by L. Elizabeth Powers

Interior design and typesetting by Susan Leonard

The text of this book is set in Warnock.

First Edition

161718192054321

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Horvath, Patricia, author.

Title: All the difference / Patricia Horvath.

Description: First edition. | Wilkes-Barre, PA: Etruscan Press, [2017]

Identifiers: LCCN 2016054248 | ISBN 9780997745573 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Horvath, Patricia--Health. | Osteoporosis--Patients--United States--Biography. | Osteoporosis--Popular works. | Self-care, Health--Popular works. | BISAC: BODY, MIND & SPIRIT / Healing / General. | SELF-HELP / Personal Growth / Success.

Classification: LCC RC931.O73 H68 2017 | DDC 616.7/160092 [B] --dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016054248

To protect the privacy of actual people, some of the names in this book have been changed.

Please turn to the back of this book for a list of the sustaining funders of Etruscan Press.

This book is printed on recycled, acid-free paper.

To my mother, who was there.

She is still asking herself where this body ought to be, where exactly to put it so that it will cease to be a burden to her.

—Marguerite Duras,

The Ravishing of Lol Stein

Contents

Acknowledgments

Prologue

Dry Bones

Testifying

Tests

Books

Silence

Earthbound

Good Girls

Caged

Allowances

Orphans

Monkey Girl

Chastity Belt

Percentages

In Hospital

Lights Out

All the Difference

Waiting

Meltings

Baby Steps

Partings

Pacifying the Beast

Straddling

Gone

Unchosen

Backward Glances

Legacy

Epilogue

About the Author

Acknowledgments

Excerpts from this work first appeared in Cream City Review and 2 Bridges Review.

I wish to thank the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund, Hedgebrook, Millay Colony for the Arts, and Blue Mountain Center for their support. Thank you, as well, to Framingham State University.

For their encouragement and sage critique I thank Robert Dow, Marita Golden, Michelle Hoover, Jane Rosenberg LaForge, Jeffrey LeBlanc, Jay Neugeboren, Kate Southwood, Elizabeth Fairfield Stokes, and Michelle Valois. Thank you to my mother, Maureen Cotter, and to my brother, Howard Horvath, Jr., for putting up with my questions. Thank you to Chris Bullard for his sharp editorial eye. Finally, thank you to the good people at Etruscan Press, most especially Bill Schneider and Pamela Turchin, for their belief in this book and their hard work in helping it come to fruition.

Prologue

I may as well admit it, I’m poorly put together. My body leans sharply to the left. I’m brittle-boned, stoop-shouldered, with an “S” shaped spine. I cannot touch my toes, ice skate, or ride a bike. My right shoulder blade and hipbone stick out too far, and my right leg is a half-inch shorter than my left. When I walk, my right foot swings wildly to the side. On its own trajectory, my foot will skim the sidewalk’s detritus: potato chip bags, stones, bottle caps. My ex-boyfriend called it my “trick foot.” We’d pass, say, a dented car or battered-looking hydrant. Look what the trick foot did! he’d exclaim and I’d laugh, wanting to be a good sport. It’s important to be seen as a good sport when one is, in fact, completely unathletic.

Dry Bones

The doctor was “astounded.”

Patient suffers from marked osteoporosis, the report read. Fracture risk is high. Treatment, if not already being done, should be started.

He told me the results did not make sense. “You have the bones of a seventy-year-old. Are you sure you don’t smoke?” “Never.” “And . . . you’re definitely still menstruating?” “As we speak,” I replied. What I wanted to say was “See? You should have believed me!” because for nearly two years I’d been insisting to skeptical doctors that I was shrinking.

Two years earlier I’d been living in Massachusetts, finishing up my MFA degree while teaching sections of freshman composition at two different schools. On a typical day I got up around seven, made a pot of coffee, and drank it over the course of several hours while I wrote, then headed to my grad courses in the late afternoon. Tuesdays and Thursdays I taught morning classes at a state college and afternoon classes at my university. Either way, sometime around noon I’d rush through a meal of yogurt and fruit. Dinner was just as perfunctory—defrosted soup, maybe a sandwich. Weekends I wrote and graded and looked for jobs. Some nights I met up with other grad students at readings or bars where we drank beer and listened to music and talked about life after graduate school, which in my case would entail a move to Harlem and an adjunct teaching job. The job would eventually grow into a full-time position, but I could not know that then. Meanwhile, I drank too much coffee, ate too little, exercised infrequently, and all the time I was slowly shrinking. I could not know that either.

Because I was graduating, and losing my health insurance, I decided it would be a good idea to get a check up. Aside from intermittent bouts of insomnia, which I’d had since adolescence, I felt fine. Nevertheless, one morning in late May I took off my shoes and stood on the doctor’s scale. I’ve always derived a certain goofy pleasure from these check-in rituals. The nurse straining on tiptoe to record my height. Or nestling the larger of the scale’s two weights into the one hundred pound slot then sliding the smaller weight too far to the right and having to guide it back—slowly, slowly—well to the left of where she’d started. The inane, jocular comments: My you’re a tall drink of water! And: I bet you can eat whatever you want.

This time, though, the nurse barely had to stretch. She rested the level against my head and wrote down a number—sixty-seven inches. But sixty-seven inches was wrong.

I’m five-eight, I said, startled. The scale’s not right.

It’s a scale.

She picked up the blood pressure cuff, waiting for me to roll back my sleeve. Other people were waiting too—a room full of patients she had to weigh and measure. This nurse was a busy woman who did not have time to indulge her patients’ whims. Still, she relented. I stood up as straight as I could. I pulled back my shoulders and lifted my chin. The vertebrae in my spine cracked as I tried, uselessly, to will them to straighten. I stretched and stretched to my full height . . . five foot seven.

But last time—I began.

You can discuss it with the doctor. Now let’s look at that blood pressure.

In the doctor’s office I changed into a crinkly paper gown. The day was unseasonably cool; I could feel goose bumps rising on my arms. I wanted my coat. I wanted to go home, get my coat, start the day over. Come to think of it, if I’d really shrunk an inch, why did my coat still fit? And my othe

r clothes, few of them new. Shouldn’t my pants be dragging the ground, my sleeves dangling?

I thought of my father’s mother, hunchbacked and tiny by the end of her life. Didn’t I take after her—birdlike in a family of big-boned people? She’d been diagnosed with osteoporosis, the “widow’s stoop,” as it had then been called. I knew the risk factors, knew they were against me: a small-boned Caucasian woman, dwelling in a northern climate and living the sedentary life of a graduate English student who’d just spent the past year teaching seven courses at two different schools while working on a book. A woman who, as a child, had loathed milk and spent her summers reading indoors. Someone whose biggest treat had been a trip to the library—not the children’s library, but the adult one where the floor was made of glass bricks lit from below and the book titles were not, I understood, to be taken literally but instead held mysterious, hidden meanings. My grandmother and I spent hours in the stacks. She craned to reach the higher shelves. We were alike in more ways than one. Still, she was my grandmother, old before I was born. Women my age weren’t supposed to shrink.

The doctor came bustling in—smiling, pleasant, visibly harried. She apologized for keeping me waiting, and she began to ask about my general health.

I’m shrinking, I interrupted. I think I have osteoporosis.

She looked at me, clearly puzzled. I’d been seeing this doctor for years. She was thorough, calm, a good listener. We’d commiserated about issues of women’s health: the needless difficulty, say, in attaining the “Plan B” morning-after birth-control pill or the nearly instant FDA approval for Viagra while RU-486, the French “abortion pill,” had been banned by the FDA for over a decade. So I was genuinely taken aback when my doctor told me no, this could not be, I was far too young to have osteoporosis. A baseline bone density exam would be conducted at the onset of menopause, perhaps another ten years. How short, I wondered, would I be by then?

I could feel a small rip opening at the back of my gown as I shifted in my seat. My thighs stuck to the hard plastic of the chair seat. I wanted to get on with the exam, but I knew I was not leaving until she took me seriously.

I’ve shrunk an inch, I said.

The doctor looked through my file. She had no record of my height. My last measurement must have been with my previous doctor, at least three years earlier. Perhaps, she suggested, that scale had been inaccurate? Perhaps I was mistaken?

I’m a shy person, soft-spoken. I dislike confrontation. On the subway, if someone vacates a seat, I’ll look around to see if anyone else needs it before sitting down. If a student comes to me upset about a grade, I’ll listen to her arguments. Sometimes I even change the grade. But this was different. This woman, my doctor, was standing between me and my health. Because the insurance industry or medical profession or whoever it was who makes these decisions had determined that women my age could not have osteoporosis, women my age were not tested for the disease. How then could I support my claim?

I told the doctor that I needed her to authorize a bone density exam. She refused, saying that premenopausal women are not at risk for osteoporosis. But my mistrust of my body—too profound for her words to sway—convinced me I was right.

Look, she said, it’s highly unlikely you have osteoporosis.

Highly unlikely or impossible?

The doctor opened her desk drawer, took out her prescription pad. Patients were backed up, waiting to see her; not yet noon, it would only get worse. We hadn’t begun my exam. She wrote something down and, unsmiling, handed me what I needed.

When the results came back, she called. The doctor said she was sorry for having doubted me, it was good I’d been so insistent. Still, I had to understand how unusual this was. I felt vindicated, but also angry. Not only at the doctor, but at myself. Why hadn’t I noticed that in three years no one had recorded my height? Wasn’t I the one ultimately responsible for my health? If I’d paid closer attention . . . then I stopped. How else could I have known? I had to shrink to realize that I was shrinking. I hung up the phone and began to cry. You’re my doctor, I wanted to shout. What if I had listened to you?

Femur, tibia, fibula—I pictured the long bones in my body crumbling to powder. The doctor had mentioned Fosomax. I’d seen the commercials: silver-haired women rode horses and did leg lifts at the ballet bar while an announcer intoned See how beautiful sixty can be. As far as my doctor knew, no studies had been conducted about the long-term effects of Fosamax on forty-year-old women. She’d called an endocrinologist at Massachusetts General Hospital who’d told her that Fosamax can remain in the bloodstream for up to seven years. Supposing I became pregnant?

The doctor recommended exercise, calcium, Vitamin D, a follow-up visit in a year. It was nearly two years, however, before I had health insurance again. This time I knew exactly what to do. I made certain I was measured. I’d shrunk another quarter inch. When my new doctor balked (Osteoporosis? Are you sure?) I had proof. Now, with a fresh batch of results showing further bone loss, he was “astounded.”

He said it was essential I start taking Fosomax. He also set up an appointment with an endocrinologist at St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital near Columbia University. Late winter, early spring I walked from my apartment in Central Harlem past the decaying buildings along Frederick Douglass Boulevard, through Morningside Park, up the hill to Amsterdam Avenue, where the neighborhood abruptly turned cleaner, shuttered buildings giving way to bookstores and cafés, welcoming beneath bright awnings. Snow melted to mud, crocuses poked through the earth, then daffodils, tulips, until the park was a riot of new growth.

The endocrinologist—British, exceedingly polite—ordered tests. Lots of tests. I had blood drawn twice, another bone density scan. For twenty-four hours I peed into a jug that I lugged back to the lab in a plastic Fairway bag. The next day I got a call—they’d neglected to give me a vial of preservatives to mix into the jug; I’d have to redo the test. Up and down the hill again with my jug of urine. When the tests finally came back, they revealed nothing—except that I had osteoporosis. The endocrinologist confessed to being “perplexed.” But I was not. My bones have always been treacherous, and once again they had betrayed me.

Testifying

I moved to New York during the first year of the new century, a boom time, though my neighborhood, Central Harlem, was not yet booming.

The sales office for my building was a double wide trailer parked on West 116th Street. The marketing director, a formidable woman with a crown of coiled braids, referred to me as her “queen.” As in: “And how is my queen today?” Like the other women in the office she was overtly religious, and on the day I signed the purchase and sale agreement for my unit, a Sunday, she celebrated by inviting me into the office staff’s prayer circle. I stood between her and the accountant in a group of a dozen or so praying, swaying women, all of us holding hands. Some of the women “testified”—about struggles overcome, family members who needed help, a son in prison, a daughter with an addiction, a diploma recently achieved, people who needed prayers of supplication or thanks. I didn’t know the words to the prayers and I had no inclination to testify, but I felt moved to be included in this circle, to have crossed some invisible barrier from client to communicant. When it was my turn to give thanks, I said simply, I’m so happy to be here.

Across the street from my new building were two vacant lots heaped with demolished car parts that glittered in the sun. The lone neighborhood supermarket had brown lettuce, sawdust-strewn floors, gangsta rap. There were abandoned buildings on both sides of every block. Crack vials crunched underfoot; I had to pay attention whenever I wore sandals. But my apartment was large and sunny, and every day, weather permitting, I went for a walk in Central Park.

I had only to read the paper to be reminded, starkly, of how my neighborhood differed from New York below 110th Street. There, people ate gold-flecked desserts in celebrity restaurants. Hermès kept a waiting list for five-figure Birkin bags. A famous woman with a famous father backed he

r Mercedes SUV into a crowd of people milling about a Hamptons nightclub while screaming “Fuck you, white trash!”

I’d known about the excess before moving, of course. Still, the contrast between where and how I lived and the antics taking place to the south was jarring. One day, I no longer recall where, I read an article about a couple who had plastic surgery and liked the results so much that they decided to have their children undergo the process, too, “So we’ll look more like a family.”

I’d been diagnosed with osteoporosis only a few months earlier, and it occurred to me that this was a serviceable metaphor for the creative person in the consumerist vortex that was twenty-first century Manhattan. So I wrote a story in which a woman, a poet, is shrinking so rapidly that she has to carry a milk crate to stand on. When she disappears entirely, no one notices.

The story, being somewhat heavy-handed, didn’t really work. It was funny, but tainted by bitterness. I knew that. Still, I showed it to some colleagues in my writing group, who asked me about the piece’s genesis.

So I told them. About my osteoporosis and then, haltingly, about its precursor, scoliosis, the years I’d worn back braces and body casts, my spinal fusion at age fifteen, the difficulty I’d had re-learning how to walk, the even greater difficulty of learning to see myself as “able-bodied.”

I’d known these women for years. We’d gone to grad school together, had met every Thursday night for dinner and workshops, and had stayed in touch when school ended.

They were astonished. We had no idea, they said. Why didn’t you ever tell us?

It doesn’t seem important anymore. Even as I said this, I knew it was a lie, a way of distancing myself from the house of cards I still felt my body to be.

That’s the story you need to write. They were adamant and unanimous.

I didn’t want to listen. These women, my confidantes, were urging me to open a door I’d nailed shut. No, I thought, I’ll never write that; it’s nothing I want to revisit.

All the Difference

All the Difference